Testing anti-patterns: Invisible code

As we’ve seen over the last several weeks, it’s remarkably easy for code to earn the badge of 100% test coverage without necessarily having a strong test suite. In each of those examples, the coverage analysis tool performed its task flawlessly: it reported exactly which portions of our code were executed as a result of running the tests. The all-green coverage report showed us that the tests indeed touched all of our code, but it was up to us to acknowledge that simply touching a line of code doesn’t mean that you’ve exercised and verified that line of code in a meaningful way. Some folks interpret this acknowledgement to mean that coverage analysis is meaningless, but that unfortunate conclusion overlooks the real benefit of a coverage report: it’s not about getting to 100% test coverage and assuming victory, it’s about highlighting any areas of our codebase that we’ve forgotten to test entirely.

As with any tool, to make effective use of coverage analysis, we need to understand its purpose, its capabilities, and its limitations. In all of the previous examples, we looked at code that was already in the coverage report. In other words, the coverage tool knew about this code and was able to watch the code and assess its coverage upon completion of the test suite. But if we’re using the coverage report to help us find untested code, how do we deal with code that the coverage tool might not be aware of in the first place?

Let’s start with a sample Rails app that represents the beginnings of an online store. The project currently contains the following files (as well as some others that I’ve omitted for the sake of brevity).

[store]$ tree

...

|-- app

| |-- controllers

| | |-- application.rb

| | `-- products_controller.rb

| |-- helpers

| | |-- application_helper.rb

| | `-- products_helper.rb

| |-- models

| | `-- product.rb

| `-- views

| |-- layouts

| | `-- products.html.erb

| `-- products

| |-- edit.html.erb

| |-- index.html.erb

| |-- new.html.erb

| `-- show.html.erb

|-- config

| |-- boot.rb

| |-- database.yml

| |-- environment.rb

| |-- environments

| | ...

| |-- initializers

| | |-- inflections.rb

| | |-- mime_types.rb

| | `-- new_rails_defaults.rb

| `-- routes.rb

|-- db

| |-- migrate

| | `-- 20080810220638_create_products.rb

| `-- schema.rb

...

|-- lib

| |-- product_ftp_importer.rb

| `-- tasks

| | |-- data_load.rake

...

|-- test

| |-- fixtures

| | `-- products.yml

| |-- functional

| | `-- products_controller_test.rb

| |-- integration

| |-- test_helper.rb

| `-- unit

| `-- product_test.rb

...

37 directories, 63 files

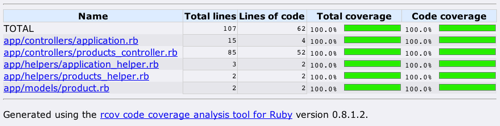

After installing the rails_rcov plugin, we can easily produce a coverage report to see where we currently stand.

According to the coverage report, we’re not aware of any code that isn’t touched by at least one test. But is that really the whole story? The number of test-related files sure accounts for a small proportion of the overall app. We can see that we have test/unit/product_test.rb and test/functional/products_controller_test.rb, but do those two files really encompass all the developer testing needed for this application?

Out of sight, out of mind?

What about that mysterious file hanging out in the lib directory?

[store]$ tree

...

|-- lib

| |-- product_ftp_importer.rb

...

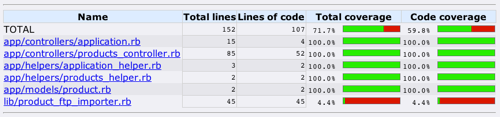

Just judging by the name of the file, that sure sounds like functionality that deserves testing, but for some reason it’s not listed in the coverage report. And if we take another look at the test files listed above, there are no test files that obviously correlate to product_ftp_importer.rb. So, how is it that we have 100% coverage?

In order for code to show up in a coverage report, we need to instruct the coverage tool to assess that file. The approach for doing so tends to vary from tool to tool. With rcov, we first have to tell it which files constitute our test suite (i.e., the files we want rcov to run). But that alone is not sufficient; we also have to ensure that application files (i.e., the files whose test coverage we want to measure) get loaded as part of the test suite. Adding this require statement anywhere in our test suite is enough to shed some light on the elusive code in product_ftp_importer.rb.

require File.expand_path(File.dirname(__FILE__) + "/../lib/product_ftp_importer")

It’s hard to feel good about 45 lines of untested FTP-processing voodoo, so how can we unearth this invisible code as soon as it tries to sneak its way into our app?

- Ensure that your coverage task knows where to find your tests, always place new tests where the coverage task can find them, and use a consistent naming scheme so that a simple file-matching pattern can distinguish test files from non-test files.

- If you’re using rcov, add a quick script that will crawl your project tree and

requireall application files. Adding individualrequirestatements one-by-one is not a reasonable solution. If someone’s not going to write the test in the first place, they’re sure as heck not gonna take the time to tell the coverage report about that misdeed. So, walk the tree and require any Ruby file that you encounter in places where application code is likely to turn up. At the very least, in a Rails app you should include all subdirectories underapp(being aggressive enough to catch any new directories that might get added there) and thelibdirectory.

UPDATE (2008-08-21) At the “How to Fail with 100% Test Coverage” talk earlier this week, a few folks asked if I’d provide an example script that would perform this task in a Rails app. Adding this line to test_helper.rb should get you started.

Dir["app/**/*.rb", "lib/**/*.rb"].each { |f| require File.expand_path(f) }

(Not so) scenic view ahead

View templates have long been a favorite dumping ground for misplaced application logic. This problem can often go undetected, because view templates fly under the radar of the coverage report. Most developers know they should minimize the application logic included in the view, but when a deadline’s looming, the lure of throwing some code in the view “just this once” is often hard to resist. For example, what’s so wrong with having the view decide whether to display a particular product in the list?

<% for product in @products %>

<% if product.quantity_in_stock > 0 && product.quantity_in_stock > product.pending_backorder_count %>

<!-- display purchasable product here -->

<!-- ... -->

<% end %>

<% end %>

Well, how exactly will we verify that the view is indeed displaying the right products and suppressing the others? We could manually test each scenario by visually inspecting the resulting UI, and that might be good enough for us to have confidence that the app is doing the right thing as of this moment. But code has a life of its own, and it will grow and change over time, and we want automated tests to make sure that this page continues to display the correct data even after those inevitable changes.

So we decide to write tests to verify that we’re displaying only the right products. And since this logic is inside our view template, we need to write tests that will render our view template and then dissect the resulting HTML to verify that it contains the products that should be present and that it does not contain the products that should not be present. But in order to render the HTML, we need to invoke some controller action. And because that lone if statement needs at least four different test cases to check the various conditions, we get the joy of doing all that setup and dissection at least four times. That’s a big enough pain that it quickly becomes very tempting to let this bit of logic remain untested, remain out of sight of the coverage report, and remain “good enough.”

We can do better than that. When something’s too hard to test, we should refactor it until it’s easy to test. [1]

We’re going to need this logic outside of the view anyway, so the sooner we get it into the model the better. Sure, the view will only display those products that are available for purchase, but we need that logic for server-side validation as well. Before we process an order, we need to make sure that we still have the product in stock. If we leave the logic in the view as is, then we’ll be forced to duplicate that logic elsewhere inside our order-processing code. There’s clearly no justification at all for leaving this logic in the view.

<% for product in @products %>

<% if product.available_for_purchase? %>

<!-- display purchasable product here -->

<!-- ... -->

<% end %>

<% end %>

When we encapsulate this logic in the Product class itself, we can test that logic in isolation, without any dependencies on controllers, and without the need for fragile HTML-parsing to verify the result. Once we perform this refactoring, unit testing the #available_for_purchase? method becomes trivial, and we can refer to that method wherever necessary without unnecessary duplication.

Better still, if we know that we only want to display the products that are available for purchase, we can ensure that our controller provides only those products to the view in the first place. With this approach, our view then enjoys the pleasant simplicity of just displaying the list of products.

<% for product in @products %>

<!-- display purchasable product here -->

<!-- ... -->

<% end %>

The coverage report isn’t going to alert us to business logic lurking in our view templates. It’s up to us to keep our views from becoming too smart for their own good, and it’s up to peer code reviews to keep us honest.

Raking for buried treasure

While it’s tempting to let our views acquire too much business logic, there’s usually an obvious place to move that logic once we realize the error of our ways. (In Rails, you’ll typically relocate that logic to a model class or to a helper, either of which are easily tested in isolation.) But what about the other parts of our application where untested code tends to hide out and germinate?

Perhaps we have some code that only needs to run at application start-up. In Rails, we’re talking about code in environment.rb or config/initializers. In Grails, BootStrap.groovy is home to this logic. In either case (or in most any other framework), we’re not likely to see those start-up “scripts” included in the coverage report, nor is there a natural and obvious place for testing any complex code that we may need to include in the start-up process. We’re used to testing models and controllers and helpers and mailers, but where does this start-up logic fit into the mix?

Data migration suffers from a similar problem. Rails migrations are great for creating and dropping tables, adding and removing columns, etc., but sometimes we need to do more than just alter the schema; sometimes we want to push data around as well. Schema transformations are essentially declarative code, and really don’t warrant anything beyond visual verification of the results. But when it comes time to migrate 10 million records from some legacy database into our hip new application, chances are we’re not just talking about simple declarations anymore. What’s the worst that could happen though? This code only has to run once. And who wants to write a bunch of tests for code that we’re only gonna run once and then throw away? And once again, there’s no obvious place for us to add tests for this kind of data conversion functionality in the first place. Surely a simple Rake task will suffice.

namespace :db do

namespace :load do

desc 'Load products from csv'

task :products do

require 'csv'

require 'environment'

CSV.open("#{RAILS_ROOT}/db/input/csv/product-catalog/products.csv", 'r').each_with_index do |row, idx|

next if row[0] == "Product"

p = Product.find_or_create_by_name(row[0])

p.description = e.purpose = row[5]

p.sku = row[3]

p.price = row[4]

p.save

shipping_options = row[1].split("|")

shipping_options.each do |o|

p.shipping_options << ShippingOption.find_by_name(o)

end

vendors = row[2].split("|")

vendors.each do |v|

p.vendors << Vendor.find_by_number(v) unless v.downcase == 'none'

end

end

end

end

end

Indeed, a simple Rake task will suffice, but that’s certainly not what we’re looking at above. While we could write tests for this logic in its current state, doing so is unnecessarily difficult. We’d be restricted to solely black box tests. To test each individual decision point, we’re forced to also construct a new file holding the appropriate dataset, run the Rake task, and then inspect the state of the data in the database. For every decision point.

Scripts can be classy too

We shouldn’t have to also test the ability to read a file (i.e., line 7) just so that we can test the ability to populate a vendor based on a given vendor number (i.e., line 21). For sure, we want one good end-to-end test to verify that all the cogs are working together correctly. But if that’s our sole testing strategy, then we’ve made testing just painful enough that it probably won’t happen at all.

Whether we’re talking about hard-to-test code in start-up scripts, hard-to-test code in migration scripts, or hard-to-test code hiding out in the handful of other custom scripts that an application tends to accumulate over time, the answer’s the same in each case. Just because the coverage report doesn’t see this hidden code doesn’t mean that it’s not worth testing. And just because our framework-of-choice might not provide a convention for testing this logic, that doesn’t mean that we should just punt.

When something’s too hard to test, we should refactor it until it’s easy to test.

namespace :db do

namespace :load do

desc 'Load products from csv'

task :products do

require 'environment'

importer = ProductCsvImporter.new("#{RAILS_ROOT}/db/input/csv/product-catalog/products.csv")

importer.run

end

end

end

In the case of this Rake task, and in each of the cases discussed above, by simply moving the logic out of the script and into a proper class (or module), the testing strategy goes from clumsy at best to downright obvious. We no longer need to invoke the whole script in order to verify the particular unit of functionality that we want to test. Instead, we test that functionality in isolation, and allow the script to resume its trivial role of merely calling our well-tested class.

Use it wisely

In order to make effective use of coverage analysis, it’s important for us to understand what a coverage report is telling us and what it’s incapable of telling us. Tools are imperfect, but we can adopt strategies to make sure we’re reaping the maximum benefit from the tools we choose to employ. With good naming conventions and an agreed-upon application structure, we can easily configure an intelligent solution that allows the coverage tool to automatically pick up any new source files that we want included in the report. With a commitment to testing all application logic - regardless of whether it’s needed in a model, a view, a script, etc. - we’ll extract the code that would otherwise be buried in a dark corner of our app. We’ll benefit from the ability to test it in isolation, and we’ll allow the coverage tool to assess that code, giving us a more realistic and complete view of our codebase.

Invisible code is hidden technical debt, but the sooner you expose it, the sooner you can start to pay it down.

Notes

[1] In past posts in this series, I’ve advocated test-driven development (TDD) as means for combatting the various testing anti-patterns. Invisible code is no exception. While this post is geared more toward uncovering invisible code so that we can give it the testing it deserves, developing test-first is the best bet for preventing invisible code in the first place.

This post is part of the Testing Anti-patterns series: a series of essays taken from a conference talk titled, How To Fail With 100% Test Coverage.

–

Thanks to Muness Castle, Justin Gehtland, and Greg Vaughn for reading drafts of this post.